A walk on the wild side of Wales

The third instalment of my journey into nature-led philanthropy

When we left our story I had joined a call about a rewilding project kicking off in Wales, the latest such calls in a long line since the start of my interest in nature restoration. This one started out in familiar fashion, throwing out percentages of habitat loss and species decline and other such general Zoom and gloom. I decided I would give the next speaker a minute’s grace then I would log out for the evening.

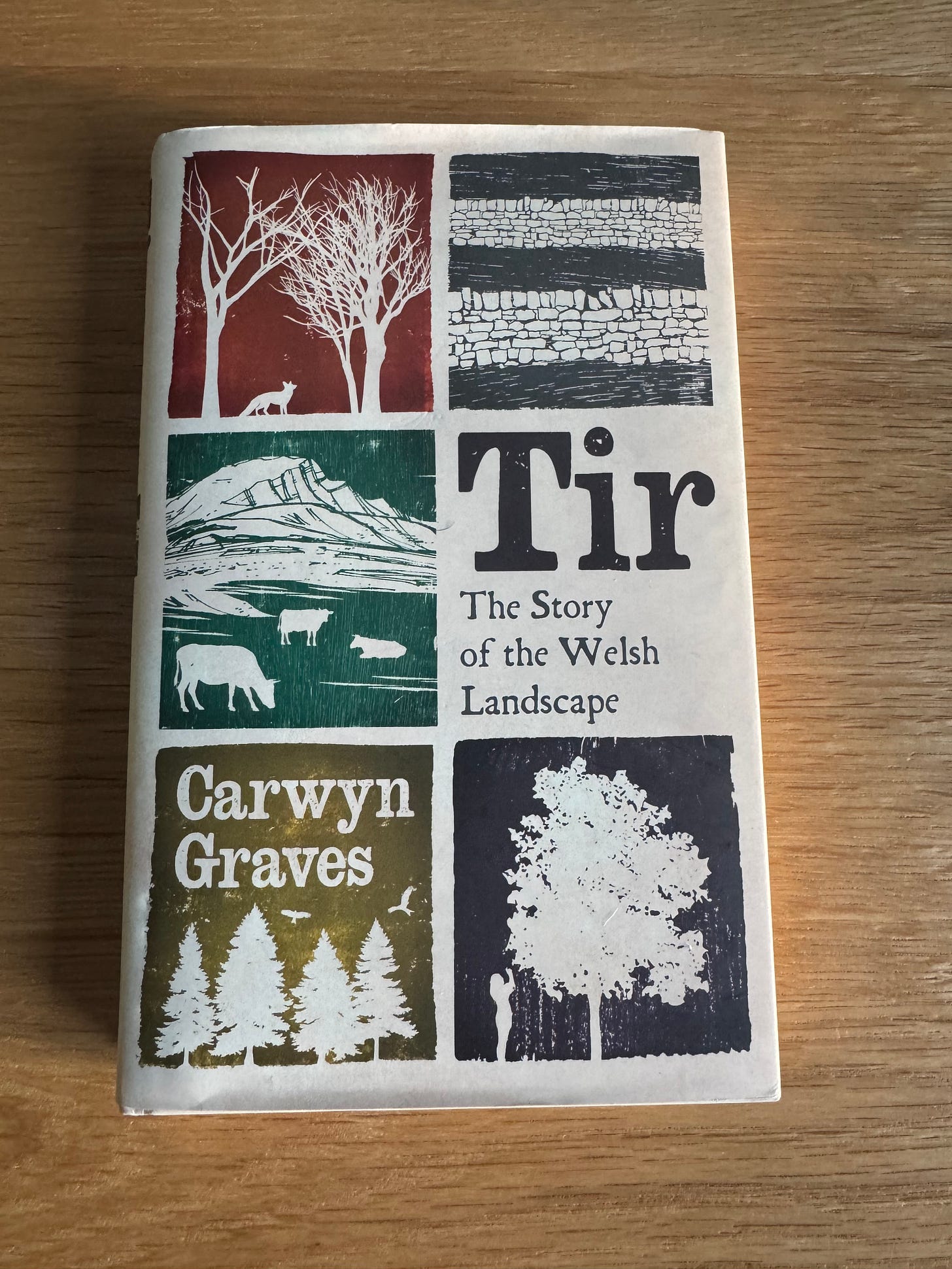

His name was Carwyn Graves and he described himself as a writer and naturalist. I had come across many of those before; indeed I have been described as such myself, somewhat erroneously it must be said on both counts.

When Carwyn started talking about Wales as a cultural landscape, I pricked up my ears. This was my kind of language. Well, not exactly my language as his talk was conducted 50:50 in English and Welsh. But as someone who had been deeply involved in the world of community ownership for the last 20 years, hearing a speaker passionate and knowledgeable about putting people and culture out front and centre stage got my attention.

And as a linguist by trade, I was drawn in by hearing a language I didn’t know that had literally inscribed itself into the land. Carwyn explained that Welsh gives names to landscapes that are literally untranslatable into English; words like Perllan (“a planted fruit-bearing woodland”)1 or Mynydd (“a mountain or moor in drier, rough grazing land”). In every way this sounded like poetry to my ears.

Enthralled, I stayed to the end of the call. I then tracked down a copy of his book and signed up for a tour of the site in question.

One brisk March day I set out from London at the crack of dawn for the train to Cardiff.

I had to sign a piece of paper in advance to promise that I would not disclose our destination as the transaction was finely poised at that point. I half expected Gwenni and David to blindfold and bundle me into the back of a blacked-out Humvee at the station. Indeed, a part of me was a bit disappointed that didn’t happen but the two hour drive was almost as exciting. The whole ride I bombarded them with questions which they sportingly batted back with interest.

As we drove along they pointed out the names of each landscape in Welsh. Here was some Coed, “native woodland used for food, shelter and rough grazing”, above Pontypridd. It bore the name of Coedpenmaen and it really should not still be about in this former mining valley after a couple of centuries by despoliation by slag, smoke and coke. Then with built-up towns far behind us, Gwenni pointed out the Cloddiau, “the hedgerows on earthen banks used as animal enclosures and a source of foraged food”.

By now the road had narrowed down to a single track as we closed in on our destination. We were in the midst of Rhos, which Carwyn Graves had defined as “heath, moor and bog, wetter rough grazing land”. It once made up 40 per cent of Wales’s land mass and “probably represented the single largest haven for Welsh wildlife for millennia”.

But that was far from being the case today.

The first thing that struck me when we got out of the car was the silence. But not in a good way.

At this minute I am sitting at my desk writing this from atop one of the busiest junctions in London, bisected by the road to Brighton whose foundations had been laid down originally by the Romans. Above the incessant traffic noise I can nevertheless hear the machine-gun rat-tat-tat of a wren defending its territory. A deafening squadron of parakeets are fanning out from their roost in Brockwell Park to all points of the south London compass. I can even catch the sound of a woodpecker coming from one of the larger gardens bordering the Brixton one-way system.

But that March day in one of the remotest spots in the British Isles, I could hear nothing of nature over the sounds of the light drizzle and a nearby stream.

It seemed to me we were the embodiment of what Carwyn described as “sheep-wrecked country”.

What spread out before us on the top of the moor was little more than a monoculture of molinia moor-grass. Well-nigh indestructible and tough as old boots.

Outside of the late spring sheep actively avoid eating these tough tussocks and so the grass ends up stifling all other growth. Wild flowers that might attract pollinators or the sphagnum moss that could re-wet the dried-out peat had been crowded out.

And it wasn’t the fault of the sheep farmers that it had turned out this way, David corrected me. These uplands had not been grazed with the intensity of the valleys. The Industrial Revolution and its aftermath has sent up quantities of soot and nitrogen that were still visible in soil samples today a hundred years later and that is what had killed off competitor grasses.

But all was not lost. Across the valley on neighbouring land there were signs of life. The levels of sheep stocking had been much reduced there over the last decade compared to the land we stood on. This had protected pioneering shrub and small trees trying to make a bid for life along a narrow stream (see the centre of the photo).

Tir Natur’s plan was to introduce (or strictly speaking, re-introduce) other livestock like cattle, ponies and pigs. They would trample and break up the thick tussocks of molinia that sheep skirt around and so plant life would break through. This was far from being a revolutionary step. In centuries past, people living on that land had just such a mixture of animals in their in-by land, the fields around their cottages.

Our enthralling whistle-stop tour of the land was only brought to a close by the fading light. I had the feeling that if we had enough head-torches between us, my guides would have served up stories and plans all night long.

Fittingly, David chose to bring proceedings to a close from the ruined walls of one of the former cottages that had formerly stood on the land.

We had not come across another soul all day but we had stumbled across plenty of evidence that people used to make this place their home. What appeared to be a bleak remote landscape that late winter’s day in 2025 had clearly been much more densely populated in centuries past.

The Acts of Enclosure that had changed the English landscape from the 18th century onwards had barely touched Wales. Efforts to drive the equivalent of the crofters off the Highlands and Islands had been actively resisted here on the Rhos with its “valuable peat, grazing, rabbits and berries”. In Wales it was the so-called little people who had won out.

Only now did I understand why the term ‘rewilding’ was such a toxic one in this country:

“…the idea of turning over vast tracts of hill country to nature by removing farming and farmers from the picture, as rewilding has often been presented by the media, is the very antithesis of all that rural Welsh culture has stood for. For speakers of a language where the talk is always of defending and upholding a threatened culture, to talk of ‘rewilding’ sounds very much like ‘killing a culture’”.

Tir Natur would not be making the same mistake as the land magnates of England and Scotland, clearing it of people, cattle and hearths. Animals would be going back onto the land as soon as humanly possible.

Although roads are sparse and public transport even sparser in that part of Wales, they already had ideas aplenty on how to develop accommodation for the popular Cambrian Way that runs along the western perimeter of the land. As well as attracting more walkers to linger here and see nature restoration in action, the army of volunteers to keep an eye on the livestock, conduct ecological surveys and help restore the lost peatland would need to have a roof over their heads. All in all, if this remote depopulated landscape were to be acquired by the charity, the variety of life to be seen on the land in the years to come, whether two or four legged would be greater than at any time in the last two hundred years.

Now that seemed to me something worth taking a punt on.

And after that trip, I indeed did. I became a Community Founding Member of Tir Natur. If my writing has inspired you then you can do the same by following this link.

The location of the land has also been revealed this week so there is no need for the cloak and dagger stuff any more.

All quotes in this piece are taken from Tir: The Story of the Welsh Landscape by Carwyn Graves.

Scottish Gaelic also has these multi-branched words. See Rob Macfarlane's "Landmarks".

One of many wonderful features of the Welsh language is a grammatical form known as the singulative. Rather than taking a shorter word and lengthening it to create a plural, Welsh sometimes does the opposite. "Coed" is a woodland, but a tree is "coeden". It's no wonder solitary trees look so lonely, when they were made to be together. I hope someday they might find their collective footing again in that landscape.