Lands of my fathers

My search for a plot of land to re-wild takes me to mid-Wales via Whitechapel, the Grand Duchy of Hesse and Cardiff Arms Park

It’s not like I have a Welsh bone in my body.

Indeed, it could be said that Scotland has a better claim to me, given my family name. I mean there is even a Gordon tartan. But it turns out that connection was spurious too.

My great-great-grandfather on my father’s side was not a Gordon. His name was Wilhelm Stein. He pitched up in the East End of London as an economic migrant in the 1860s, fleeing rural poverty in what was then the Grand Duchy of Hesse, now part of Germany.

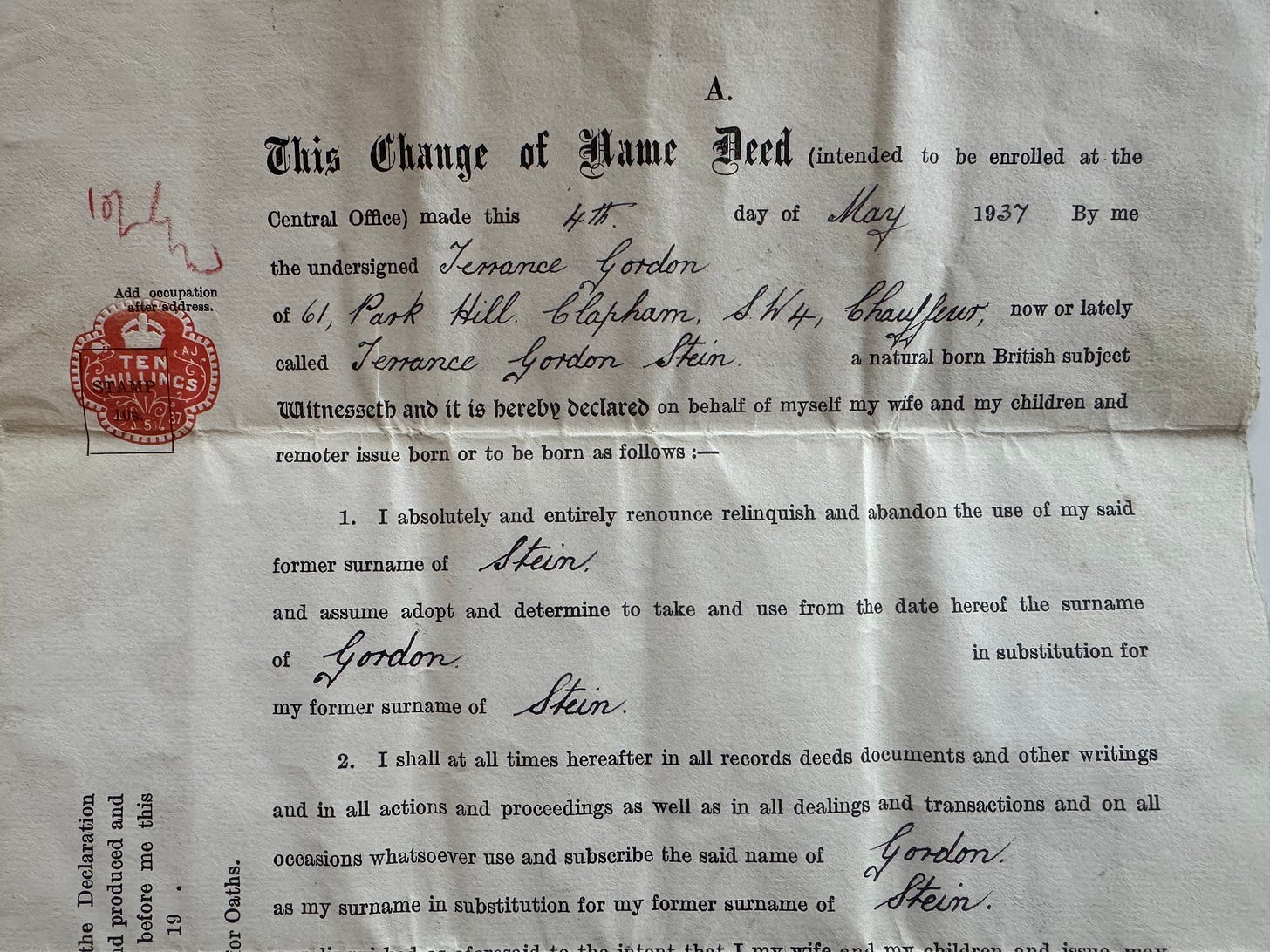

Two generations later, Wilhelm’s grandson, my grandfather Terry dropped his last name and replaced it with his middle name. That’s why my father Maurice was born a ‘Stein’ but became a ‘Gordon’ when he was six years old.

It was 1937 and the storm clouds of war were in view. It wasn’t a great time to have a recognisably German name. The father of that more famous ‘Stein’, Rick the chef, recalled that his father used to have bricks thrown through his window to shouts of ‘filthy Bosh’. But they held onto their name.

My own grandfather didn’t though. He went in the opposite direction. Indeed some might say that Terry overdid it on the assimilation front.

Not only did he drop the last trace of his German roots. His parents had given him that ‘Scottish’ middle name at a time when the local MP was Major Sir William Eden Evans Gordon. Was that mere coincidence?

Gordon was elected on an anti-immigrant ticket to one of the poorest and most diverse constituencies in the country, where my forebears the Steins lived. As a ‘restrictionist’ he wrote a book called ‘The Alien Immigrant’ where Whitechapel, my grandfather’s birth place, is portrayed as a ‘foreign town’ dominated by Eastern European Jews escaping pogroms in Russia and Poland.

It is pure speculation on my part as to whether my grandfather’s middle name had anything to do with the name of the local MP. But dropping ‘Stein’ to replace it with ‘Gordon’ would be like a Bangladeshi today in the same district of London deciding they were no longer a ‘Hossain’ but a ‘Farage’1.

In fact, the denial of his roots went even one level deeper.

When we were children we were led to believe we were part Jewish through the Stein branch of the family. We knew we weren’t properly Jewish as this came through our father’s line only. But the powers of auto-suggestion were such that we felt Jewish enough. That was a good thing and it made us feel a tiny bit more exotic and interesting growing up. It was only when I researched that line of the family that I found out that this too was made up.

20 years ago I made a visit to the National Archives in Kew where I found Wilhelm Stein’s naturalisation papers which revealed that he came from Hähnlein, a village near Frankfurt. I took a trip out there to see what traces of him remained. I had been kindly helped by an official at the town hall, a distant relative who had mapped out the Stein family tree back two further centuries to the Thirty Years War.

I asked him at what point the Steins converted to Judaism.

“You don’t have Jewish ancestors”, he asked. “If we Steins were Jewish then that hardware store over there bearing our name would not have been there all this time”, came back his allusive reply as he pointed to the other side of the road.

It turned out that my father had grown up with the story that they were Jewish in the 1930s as Terry thought it was better to be thought Jewish than German in London at that time. His over-assimilated father eventually got the chance to fight the Germans in 1940 but that’s a story for another day.

Nearly a year ago, the charity Rewilding Britain invited me onto a call about a project based in mid Wales that they thought would be right up my street. They were aware that I wanted to invest in land that could be restored for nature. I had not had that much to do with Wales over the years but my few associations with the country had all been memorable ones.

My first contact was through my father’s stepfather Bert, who migrated from Barry Island (of Gavin and Stacey fame) to the north west suburbs of London, looking for work as a gas fitter. I remember him as a genial man with a warm accent and a roll-up to hand who always had a comic and sweets ready for us when we went round to see him.

Then there were the three Welsh farms I had recruited to Feather Down, the glamping pioneer I brought over from the Netherlands 20 years ago.

They were Pant yr Hwych near the Ceredigion coast at Aberaeron, Pant y March perched above Lake Bala and Glanmor Isaf opposite the Isle of Anglesey in the shadow of Snowdon. The farmers there taught me a lot about Welsh culture, language and hill farming and they all pulled in consistent five star ratings from the urban families they hosted. Take a bow Martin, Llinos and Owen!

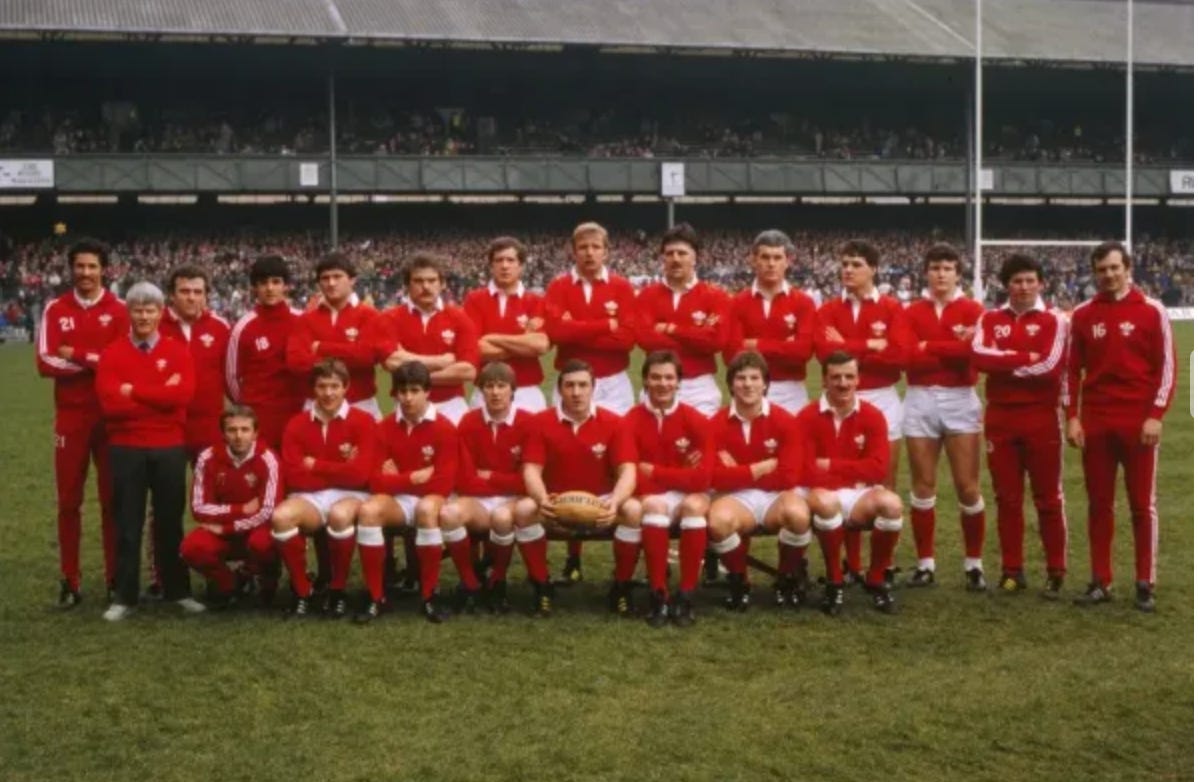

But I have to say, my most intense experience of what it means to be Welsh was in 1984 when I attended the annual clash between the Welsh and English rugby teams at Cardiff Arms Park. At the home crowd’s pre-match rendition of ‘Cwm Rhondda’ or ‘Bread of Heaven’ as it is better known in England, I realised I had tears streaming down my face. This was the opposition’s national anthem! Luckily England’s 21-16 victory helped me get over my conflicted feelings.

I learnt on that call in early 2025 that the people behind Tir Natur (‘Nature’s Land’ in English) had set up a charity to buy over 1,000 acres of knackered-out upland in some of the most remote countryside in Britain. Wales is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, according to Iolo Williams, the Springwatch presenter and ambassador for the charity who opened proceedings, 16 places from the foot of a league table of 240 countries. Just 4,000 hectares of its land has been left to be restored to nature, compared with over 100,000 in England and 160,000 hectares in Scotland.

The longer the Zoom call went on, the more my imagination was fired up. The passion of the Tir Natur team was tugging on my heart strings just like the home crowd at the rugby match in Cardiff forty years earlier.

But they were looking for an awful lot of money to buy the land. I took a deep breath in. I realised I needed to find out more before my head could catch up with my heart.

To be continued…