Life and death on Wormwood Scrubs

Villains, migrations and my father's final hours

The Central Line train had been stuck between White City and East Acton for ten minutes now. Through the darkness and the pouring rain I could just make out the gates of Wormwood Scrubs from the railway embankment; a sight both ominous and iconic. Its gatehouse used to feature in the opening credits of the 70s sitcom ‘Porridge’ and whenever there was a front page headline on prison breakouts, spy swaps and penal reform.

But that wasn’t why my heart was racing. After all, ‘the Scrubs’ had been a part of the landscape of my west London childhood. Rather, it was the message my sister had left on my phone: “I can’t handle this again. You need to come right away”.

That afternoon my father had collapsed in the street near his home. His heart had stopped for 20 minutes but the ambulance crew had managed to get it started again. It was only a matter of months since my mother had collapsed close by outside Westfield shopping centre. Her rapid descent through an incredibly brutal form of Alzheimer's ended in her death three months later.

My father was taken to Hammersmith Hospital, which isn’t actually in Hammersmith. Just as Charing Cross Hospital, where my mother was taken is not in Charing Cross. It’s in Hammersmith. Despite all the confusion I worked out where to go.

The heart unit there has views of both Wormwood Scrubs prison and what was now known as The Linford Christie Stadium. Back in the 70s, it was the plain old West London Stadium. Our running club would train there on Wednesday nights. We would share the warm-up track with a young Linford, then just one ‘Jack the Lad’, a bit of a tearaway in the sprint group. We couldn’t know then what heights he was destined for, let alone that the track would eventually bear his name.

It was clear that Thursday night that my father’s coma would be final. You don’t come back when your heart has stopped for 20 minutes. None of us were under any illusions about that.

Things were strung out for a couple of days. They proved to be some of the most memorable in our family’s history.

A shifting cast of three generations gathered around and sometimes on my father’s bed. His breathing was metronomic thanks to the ventilator. He looked like he had just dropped off to sleep in the middle of the party. In the last hours, beers were cracked open and each of us told stories from the life of Maurice or Mo, as he was known for short. He was to all intents and purposes dead but I hoped that he could hear us and our often joyous chatter. I would love to go like that, eavesdropping on my nearest and dearest at my own wake.

48 hours after my father’s collapse, the consultant said we could let him go now. The drugs and gadgetry keeping him alive could be gradually withdrawn. I was clear in my own mind that I didn’t want to witness the life support being powered down so I left my brother and sister there. I wandered out of the hospital for some fresh air.

Just two minutes walk away was that track I had known so well in my youth. With just a small rundown stand on one side, I thought it was stretching it to call it a stadium. The place was looking a lot tattier and distinctly more unloved than I remember it.

In my memories it was a place of endless summer, blood sweat and tears and laughter. I could hear the bell to mark the last lap of my distance, the 800 metres and walked back to the ward for my father’s last lap.

When I re-joined my siblings, life had left my father. His cheeks were pale and sunken and a single tear ran down his cheek, a lacrima mortis. I had thought that only ever happened in the movies.

It was a while before I could return to the Scrubs. When I did it was not the memories that brought me back.

I had since read David Lindo’s The Urban Birder. Until that point I had thought that there were just football pitches stretching north from the hospital where my father had died. But for David this was his “inner city Fair Isle”.

He was brought up in nearby Wembley and his love of birds brought him there on a regular basis during his childhood. In a chapter entitled Wormwood Scrubs - In For Life David lists some of the 140 birds he has seen in this designated Local Nature Reserve.

My first impression as I got off the train at East Acton once more was how hemmed in the space was by the arteries of London.

The hum of the Westway, the elevated section of the A40 made famous by the Clash, my childhood route ‘Up West’ marked the southern boundary. Over the years the north side of the Scrubs had been chipped away at successively by Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Western Railway, the depot for the Eurostar rolling stock, the Elizabeth Line and now the Old Oak Common complex accommodating HS2’s entry into London. And despite all that salami slicing, nature was holding on.

After the football pitches and the prison the first thing you notice is scrub, the actual scrub that gives its name to the place. Hawthorn, blackthorn and elder interspersed with thin stands of trees, the remnants of the Great Middlesex Forest that stretched from the city walls out to the north-west suburbs where I grew up. It ain’t pretty in a Chelsea Flower Show sort of way but this habitat is an immensely valuable habitat for wildlife.

In the spring and autumn birds on migration use the Scrubs as a refuelling point, hopping from one clump to the next along an interconnected corridor full of food and shelter.

On my spring visit the warblers were deafening, despite the man-made construction and cacophony around them. Scratchy whitethroats and melodious blackcaps, our ‘northern nightingales’ dominated the airwaves. I was surprised to pick up reed warblers too, despite the lack of water or even reeds, proof that these birds would be en route again once they had got their strength back.

It was not surprising that all this life had attracted predators. I spotted half a dozen kestrels on patrol and well-fed foxes foraging for the eggs and fledglings of ground-nesting birds like skylarks.

Amidst all that life, I had temporarily forgotten that the Scrubs were a deadly landscape. As I walked back to the tube station, I literally stumbled across this.

Not a hundred yards from full-blooded nature, this kerbside memorial commemorated the spot of one of the most notorious murders of the 1960s. In the ‘Massacre of Braybrook Street’, as it became known, three members of the police in plain clothes were shot dead by Harry Roberts and two accomplices, who feared the stash of weaponry in back of their van was about to be discovered.

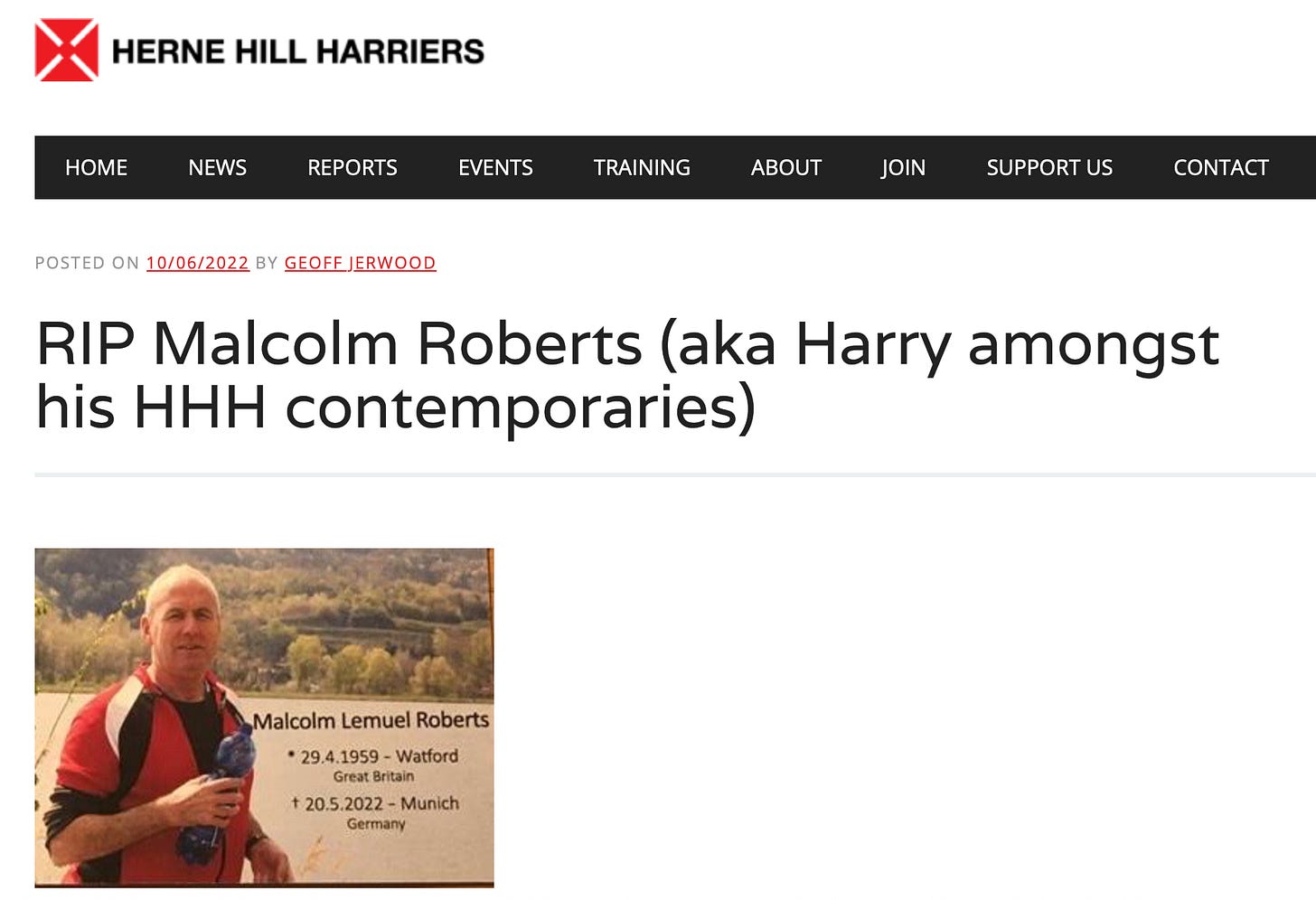

One of the stalwarts of our running group at West London Stadium was called Harry Roberts. That wasn’t the name he was born with. That would be Malcom. Our coach nicknamed him Harry Roberts; that’s how notorious he was even ten years later. Not because Malcom was a ‘dodgy geezer’. Far from it. He was a gentle guy who became a train driver on the Metropolitan Line shortly after that, his chosen career for the next 43 years. As the tribute page from his running club makes clear, that name stuck with him till the day he died.

Despite so much death about, it may surprise you to learn that I intend to return to Wormwood Scrubs on a regular basis. It is one of the most biodiverse places within Zone 2 of the tube map, both scrappy and a scrapper when it comes to nature hanging on by its fingernails. I think the place is my memento mori, the skull I don’t keep on my desk, a reminder of good times and bad and of the impermanence of life.

Markie - a beautiful piece of writing. Love the threading of the different themes around your Dad: life and death; mankind and wildlife; freedom and imprisonment; past and future. Didn't know you hung out with the young Linford. Beautiful detail about Mo being at the centre of a family party, in his final hours. Chapeau!

🤗