Death on the Kentish marshes

The third in an occasional series on rewilded places out east from London.

“I need a decision from you now”.

One of a seemingly endless carousel of doctors at the West Middlesex hospital was on the phone. He sounded really stressed out.

“But my sister will be there in less than an hour”, I pleaded.

“We can’t wait. We need your power of attorney right now to give us permission to feed your mother through a tube”.

It clearly couldn’t wait.

I said ‘yes’.

What else could I do?

Despite only just arriving, I turned the car around and headed back to face the next crisis in my mother’s decline with Alzheimer’s.

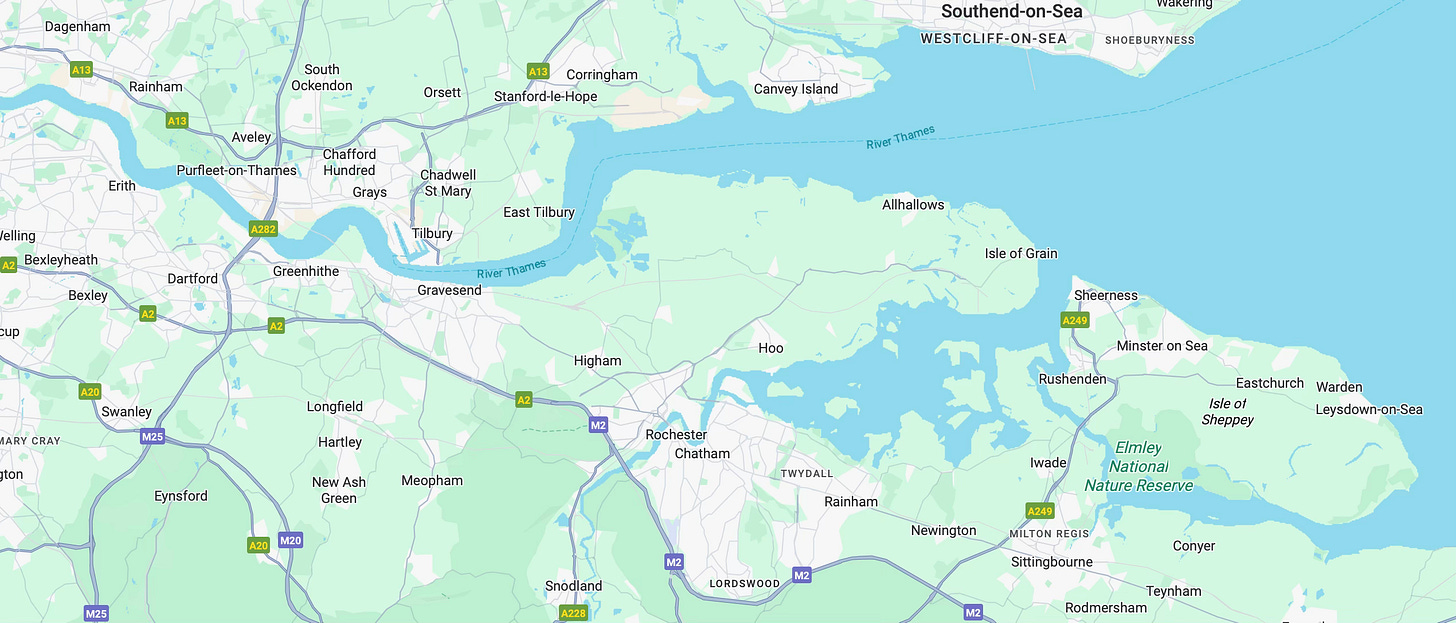

I had picked out Elmley for my day off. It looked wild and not too far to drive. Taking up the southern edge of the Isle of Sheppey on the Kent side of the Thames Estuary, the place had an interesting looking history.

Owned by Oxford University, forty years ago they passed Elmley over to the family that had farmed the 3,000 acres of grazing marsh for generations. After a brief period under the stewardship of the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds), the Merricks took its conservation back in hand. Nature was going to be front and centre stage.

Elmley is now the largest National Nature Reserve in England that is owned and run by farmers. What’s more, it is a proper business. You can book out shepherds huts and log cabins for stays. They can even stage your corporate event or wedding.

A year after that traumatic phone call, I decided to return to Elmley, this time without a car.

One December morning I took the train to Swale, the last station on the mainland and headed towards the coastal path round the southern edge of Sheppey. Facing me was a similar view to Canvey Island on the Essex side of the estuary - gas holders, scrap metal yards and cement works.

Despite the similarities between those post-apocalyptic landscapes, Kent and Essex could not be more different in the popular imagination. The latter is the home of materialistic ‘Essex man’, whilst the former is ‘the Garden of England’. The last tangle of steel structures opposite me at Sittingbourne is rapidly succeeded by the orchards of Teynham with its cherry, apple and pear trees.

But wildlife knows nothing of human stereotypes and prejudices. Both sides of the Thames Estuary sit on the East Atlantic Flyway and so both see their fair share of the 90 million migrating birds heading from north to south and back along the east coast each year.

Nor does the world of cinema, apparently.

The opening of Great Expectations from that great man of Kent, Charles Dickens, is set in the marshes around Cooling, on the Hoo Peninsula. On the map above it looks like it is trying to separate the squabbling islands of Canvey and Sheppey.

The churchyard of St James’ there still holds what has become known as ‘Pip’s Graves’, the forlorn gravestones of 13 babies that Dickens describes as “little stone lozenges each about a foot and a half long, which were arranged in a neat row beside their [parents’] graves”.

However, when it comes to bringing Dickens to life, Kent and Essex are interchangeable.

A recent BBC adaptation of Great Expectations was filmed in Tollesbury Wick on the Essex coast. Ray Winstone plays the escaped convict Magwitch. In an early primeval scene, he looms out of the mists of the marshes after escaping from a prison hulk moored off-shore.

Where he emerges is a spot I know and love from my frequent walks and stays on the Essex marshes.

Back in Kent, I continued my walk in the brisk winter sunshine along the coastal path, past flocks of redshank, godwit and dunlin till I came to a path that cut back up to Elmley nature reserve. The car park there was the setting for a display of short eared owls, seeing off a marsh harrier that had strayed onto their territory as dusk fell. I was already hooked by the place.

But it was time to head back to the station. To continue on my circular route I set off down the driveway where I had had to turn around the car a year previously after that frantic call.

Just as I got into my stride, in my peripheral vision I could see a warden gesticulating in my direction.

“You can’t walk down there”, she said.

“Yes I can”, I replied indignantly. “This is a public footpath and a right of way” I said, jabbing my finger at the OS map on my phone. “And besides there are cars going up and down the road.”

“Yes, you are perfectly within your rights to walk down that road but we would prefer it if you didn’t, for the love of the wildlife”, came the intriguing reply.

She explained to me that the lapwing and curlew on the marshes were totally habituated to cars. For them they were like slow-moving metal cows in the landscape. However a human on two legs was deemed a threat and the birds could be spooked enough to abandon their habitats.

Fiona was a retired nurse, now volunteer warden who lived in Shepherds Bush in west London. We got talking, me bombarding her with dozens of questions about this fascinating place. She kindly offered to drive me (slowly of course) back down the road through flocks of wading birds in numbers that I had rarely seen in England. We parted at the gates the best of friends and I walked back to the platform at Swale where I was treated to a starling murmuration and a kestrel harrying a marsh harrier as night fell.

The following day would be the first anniversary of my father’s death. Nine months previously to that, my mother had died, just days after that frantic call from the hospital.

Inserting the feeding tube was a postponing of her inevitable end, a sign that her body wanted to call it a day. More food was pointless but it didn’t stop our way of death prolonging her agony. In fact, the tube I gave permission for them to insert had inflamed her lungs and brought on ‘aspiration pneumonia’, the first item on her certificate as a cause of death.

I made the vow there and then as I left the Isle of Sheppey that I would draw up an expression of wishes that made it clear that forced feeding was not for me, should it come to that.

And that when I finally succumb that my remains will be scattered on one of these rewilded spots along the Thames estuary that I return to time and time again.

The ‘like’ here really means ‘appreciation.’ Of the beautiful place but also of the memory and its accompanying regret.